Direct Link Seen Between Crime Rate and Interest Rates in U.S.

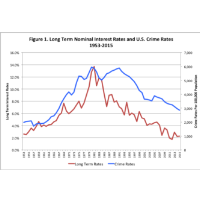

Long term Nominal Interest Rates and U.S. Crime Rates, 1953-2015 (graphic: Uniform Crime Reports, Federal Reserve Board)

Long term Nominal Interest Rates and U.S. Crime Rates, 1953-2015 (graphic: Uniform Crime Reports, Federal Reserve Board)

By James Austin and Gregory D. Squires, Crime Report

Crimes rates have plummeted in the U.S. since the mid-1990s. Most of the credit for this remarkable trend has been given to an enlarged criminal justice system—largely more police, tougher sentencing and a massive prison complex.

But we have found a larger and much more powerful explanation: A drop in interest rates and, in particular, long-term interest rates.

When interest rates go up, crime goes up. When interest rates go down, crime goes down.

This has been the case in the U.S. at least since 1953. And it is almost a perfect correlation (.77, with 1.00 being a perfect correlation).

Today, both crime rates and interest rates are at historic lows. Conversely, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, both reached historic highs. Rarely does social science research yield such a high statistical association and strong relationship between two phenomena, particularly when they are not intuitively related.

What accounts for this startling finding? What does it mean? And how might it inform public policy?

One critical implication is that lower interest rates mean not just lower crime rates, but also greater economic prosperity.

Nobody would suggest that high interest rates directly cause crime. But there is a wealth of evidence on the causes of crime that demystifies this seemingly baffling relationship. The key word is “stress”—both on an individual and societal level.

Criminologists have long known that when individuals find themselves in difficult circumstances they are more tempted to resort to unlawful activities than when their lives are more routine and stable.

And when communities face financial stress, crime rates are more likely to rise.

When interest rates rise, it is more difficult for businesses to borrow the money they need to expand their operations and, consequently, the number of jobs they can create.

High interest rates can dampen economic activity generally, which reduces consumer spending and, in turn, business receipts.

On the individual level, borrowing money becomes more expensive, credit card purchases are more difficult to repay, and daily life becomes more difficult.

The result is often not simply a reduction in job growth—but cutbacks. Employers have to let workers go, thereby increasing unemployment rates and fueling the severe stress associated with job loss.

Job loss or the expectation of a long spell of unemployment can lead some people to abuse drugs and alcohol, commit theft, burglary, robbery or worse.

Social scientists from various disciplines have long reported that when unemployment rates rise in a community a host of social problems are exacerbated.

Suicide rates, alcoholism, divorce, domestic violence, and other forms of criminal activity are just some of the increasing social costs confronting communities with high unemployment rates and other measures of economic stress.

In Social Stress in the United States, criminologists Arnold Linsky and Murray Strauss found in the 1980s that states with higher homicide and suicide rates had higher levels of social stress, as measured by such factors as business failures, personal bankruptcies, and unemployment claims.

Pooja Gupta reviewed the scholarly literature on the effects of unemployment, joblessness, and underemployment earlier this year, and found that such job-related problems contributed to higher crime rates, health problems and other quality-of-life challenges.

Interest rates also directly affect the cost of housing and particularly the opportunities for home ownership.

When interest rates rise, it is more difficult to obtain a mortgage. Developers seek higher rents to cover the costs of the homes they are building, or projects have to be cut back. Reductions in supply increase the costs.

Thus, when interest rates rise, so do housing costs for both owners and renters. This places even more stress on families who are already paying more than they should for housing.

According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard, households paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing are considered cost-burdened. In its 2016 State of the Nation’s Housing report, the Joint Center noted that 18.5 million homeowners and 21.3 million renters were cost-burdened in 2014.

Employment and housing are the two most critical markets that determine the cost of living for most families, but rising interest rates leading to higher prices for virtually all goods and services contribute to the stress of millions of households.

Considering the evidence on how long-term interest rates are related to crime rates (and other social problems), the future is mixed. On one hand, the current economic trend is for interest rates to increase very slowly if at all. The European markets suggest no long-term increases and the Asian markets led by China are quickly stabilizing.

Should these trends continue, it would suggest that crime rates will continue to remain at historically low numbers.

On the other hand, there is evidence that interest rates in the U.S. are starting to rise— and may accelerate if the national debt expands quickly under the new administration. Certainly, the consequences of cutting taxes without an associated increase in economic growth will also raise crime rates.

The influence of interest rates actors on crime rates, along with the impact of crime on the economy, should wean policymakers off their addiction to imprisonment as the most effective means for maintaining public safety.

Unlike the relationship between interest rates and crime, the relationship between imprisonment and crime rates for the same time period (1953-2014) is much smaller (a correlation of only .15).

Further, the imprisonment trend consistently lags behind the increasing crime rate from 1965 to 1993 and the declining rate thereafter. This is consistent with other studies that have shown little impact of increased incarceration on crime rates. In fact, incarceration often leads to increasing crime rates.

Linsky and Strauss, Todd Clear, and other criminologists have found high incarceration rates serve to destabilize communities by removing fathers, workers, and other contributing citizens who have committed minor violations like recreational use of marijuana from those communities, causing crime rates to rise.

Crime rates are linked to social and economic pressures and structures. That is, they reflect and reinforce various social phenomena that are not subject simply to the choices that individuals make.

If we want those who are engaged in criminal activities to make other decisions, we need to create less stressful environments that are conducive to different decisions.

Access to well-paying jobs, decent and affordable housing, adequate education, public transportation, healthy food, guaranteed health care, smaller and planned families are all factors that reduce stress.

Interest rates constitute one of the best predictors of crime rates.

We should recognize that lower interest rates nurture a more stable and less stressful society, one that suppresses crime, violence, suicides, drug addiction and other social ills in part because of the greater economic prosperity that is generated.

We have tried mass incarceration. Perhaps it is time to pursue a path that is less stressful.

James Austin is a criminologist and President of the JFA Institute. Gregory D. Squires is a professor of sociology at the George Washington University.

To Learn More:

The ‘Startling’ Link between Low Interest Rates and Low Crime (by James Austin and Gregory D. Squires, Crime Report)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Can Biden Murder Trump and Get Away With it?

- Electoral Advice for the Democratic and Republican Parties

- U.S. Ambassador to Greece: Who is George Tsunis?

- Henry Kissinger: A Pre-Obituary

- U.S. Ambassador to Belize: Who is Michelle Kwan?

Comments